Background

For over three decades, HTTP has been the backbone of the World Wide Web (henceforth referred to as “the Web”), serving as the primary protocol for transferring documents. This long history has drawn significant attention from web experts. Through successive iterations, many of its empirically derived flaws have been addressed. Enter HTTP/3---the latest iteration designed to solve key bottlenecks in HTTP/2 communication.

The evolution of the Web since the launch of HTTP/2

HTTP/2, the predecessor to HTTP/3, primarily intended to address problems surrounding “supports all of the core features of HTTP but aims to be more efficient than HTTP/1.1.” [1, Section 2].

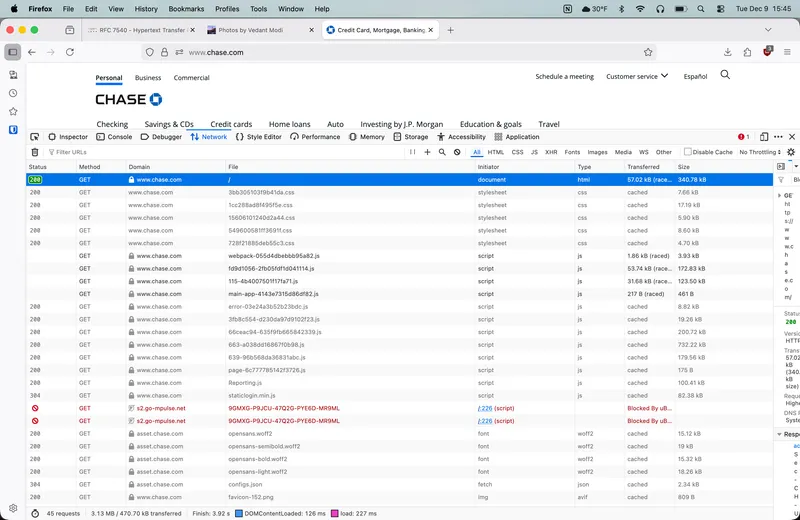

A strong feature of HTTP/2 is that it enables multiplexing [4] at the application layer (of the OSI model). This utility of this request pattern has been very common on the Web, as webpages have evolved from single file documents. Instead, loading a webpage with an HTTP GET request can involve several files such as script files, images, and the document itself. For example, chase.com will perform around fifty requests when resolving a browser’s HTTP GET request. Many of these files are a few hundred kilobytes, and therefore processing one completely before moving onto the other would result in high response times.

The GET requests that are resolved by loading chase.com in Mozilla Firefox version 145

HTTP/2 also reduced the request header payload, decreasing the number of bytes sent over the wire. The protocol introduced a slight shift away from HTTP’s traditional statelessness toward a degree of statefulness in the interest of performance. That is, the protocol will maintain common fields in the HTTP request for a given site, and the clients will not need to send common headers between requests in the same context. [1, Section 4.3; 2, Section 1.1]

Limitations of HTTP/2

HTTP/2 was proposed in 2015. Since then, members of the IETF have identified performance limitations in the protocol. In particular, the revised RFC for HTTP/2 notes that the HTTP/2 lives at the application layer of the OSI model and “allows interleaving of messages on the same connection.” It goes on to say that “TCP head-of-line blocking is not addressed by this protocol.” [1, Section 1]

As an aside, head-of-line blocking is the latency that occurs when processing packets at the front of the queue stalls the rest of the queue. [4] The problem of head-of-line blocking at HTTP’s layer was solved by HTTP/2, since its ability to process messages in arbitrary order allows a ready-to-process request to proceed without being delayed by another request that is stalled.

However, this issue is still present at the transport layer in the TCP protocol, and therefore, represents a limitation in HTTP/2. This can be understood as a leaky abstraction in the sense defined by Joel Spolsky in his article “The Law of Leaky Abstractions.” Here, the abstraction leaks because there is only so much optimization that could have been drawn from multiplexing at the application layer. Therefore, to further optimize the protocol’s procedure, some work needs to be done at a lower level, like the transport layer.

In particular, the HTTP activities, requests or responses, are all made across a single TCP connection which is set up by the client [1, Section 2]. This fact “leaks” to the application layer because there is still head-of-line blocking caused by TCP.

TCP, here, suffers from head-of-line blocking since it needs to maintain the reliability of the data stream. That is, if there is a lost packet, it must resolve the transmission of that packet before moving onto the next packet. Therefore, since all the transmitted HTTP activities have to live on this stream, any packet that needs special handling (e.g., retransmission from the sender) will delay all the other packets, including ones belonging to different documents. Therefore, the performance of one request or response is still dependent on the performance of another.

Because of this leak, optimizing at the application layer is not enough, and further optimization must be done at the transport layer. This is a concern that HTTP/3 greatly addresses with a new protocol built over UDP, QUIC.

QUIC

QUIC is a protocol that was developed in 2012, and later standardized by the IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force) in 2021. [5] In the RFC, it’s described that QUIC is a stateful interaction between a client and server, although communications using the QUIC protocol are sent as UDP packets, a stateless protocol.

Multiplexing in QUIC

QUIC promises to fix the issues of head-of-line blocking that were experienced at the transport layer by HTTP/2. Per the RFC, there is multiplexing done here, which was not done within the TCP layer.

In this way, the protocol is able to send packets belonging to different requests (or streams) across the wire using QUIC without a stalled packet in one stream holding up the processing of packets in any other stream.

In particular, a key invariant that differs between TCP and QUIC is that packets no longer need to be delivered to the receiver in the exact order in which they were sent, provided they belong to different streams. [5, Section 2] Therefore, retransmission of a packet in one stream is not a blocking maneuver for packets in any other stream, because the queue will be able to safely, and independently, process packets in another stream.

The packets will still need to be blocked in the stream with the retransmitted packet to maintain order, but every other stream/request will be able to operate as normal.

Therefore, head-of-line blocking at the transport layer is much less common in connections built over QUIC than those built over TCP.

Setup process of QUIC

QUIC, similar to TCP, provides an ordered stream to an application [5, Section 2]. However, there is not a “three-way handshake” routine like in TCP. [5, Section 2; 6, Section 3.5]

In the QUIC protocol, n-RTT refers to the number of full round trips required to complete a particular procedure---such as connection establishment or key updates. For instance, QUIC’s standard handshake completes in 1-RTT, while using resumption and 0-RTT data can reduce this to 0-RTT for subsequent connections. [7]

QUIC advertises that its setup handshake is 1-RTT xor 0-RTT. [7, Section 5] A 1-RTT handshake constitutes a first-time connection between the client and the server. Here, the handshake will perform the routines needed to establish a TLS-secured communication [8, Section 4].

Once this handshake is done, a new connection from the same client can be set up in 0-RTT, meaning that the client can send a resumption message with the connection ID, a way that clients and servers can remember each other’s communications and reestablish a connection that uses the same encryption secrets. Along with the resumption, the client can begin sending data in the same negotiation, and the server can start processing the data.

0-RTT handshakes in QUIC are very useful since changes in the identifier at a lower layer of the OSI model, such as an IP address change during a session between a user and the server, will not cause the whole of the session to reset again. Therefore, slower routines like the TLS handshake are completely avoided.

The RFC also mentions that, often, there is not a need to exit gracefully, but instead other options can be considered such as sending a message that can terminate a connection whenever that machine has lost its data to communicate.

TCP [6] cannot perform these same optimizations, as it must make the handshake to establish the sequence identifiers. It also only maintains state using the identifiers from the lower layers and is therefore highly sensitive to change and must restart the connection upon reconfiguration of the lower layers.

TCP is also not able to exit as gracefully as QUIC. It’s not possible to send a message like the aforementioned stateless flush message that QUIC can do. Since TCP needs to know the ordering of packets, the protocol will not send a packet on a connection that, to the system’s knowledge, has not had the handshake done. [6] In the case of a crash where the data to communicate from machine to machine across the transport layer and below is lost, the system will not know that the handshake has been done, and will have to redo the handshake.

QUIC, therefore, is a transport layer protocol that offers significant optimizations. This was achieved by configuring the lightweight IP wrapper, UDP, to implement useful features of TCP + TLS, like byte ordering and secure transmission channels, but with improvements in setup and teardown such that the throughput of data across a QUIC connection will be more than data across a TCP connection.

Where might QUIC be useful?

Clearly, QUIC has been used successfully to establish interactions between the clients and the servers of the Web. Moreover, QUIC was able to do this because of the aforementioned optimizations in the setup and concurrent processing of packets. The optimizations to account for changing of identifiers have proven to be particularly helpful in mobile networks, where connections change more constantly than the desktop computers that the Web started on.

These devices will change networks as they join various WiFi networks, or switch between cellular towers. On the other hand, the users of them expect the network connection, and access to the Web, to be available at all times. QUIC is able to deliver on this promise with its session resumption technology.

Also, this feature is key to the success of the QUIC protocol (spoiler) as users in many developing regions in our world primarily access the Web through cellular networks, or various public WiFi networks.

QUIC will also provide a workflow to processing several streams of packets with reduced latency. This is helpful to the situation discussed in the limitations of HTTP/2. That is, QUIC will perform well on concurrent requests to many resources needed to load the contents of a modern webpage.

Again, using this protocol will benefit those in developing regions, as they will be able to access modern webpages. With the lower response times on modern webpages provided by QUIC, there will be less need to explicitly design pages with simpler features. In fact, Google, who backed QUIC’s development, removed the “Basic HTML” view of gmail.com in favor of the modern version, which GETs over one hundred scripts alone when the landing page is loaded.

Therefore, a communication protocol built over QUIC might be useful to browse complex, large websites on mobile networks better than its predecessors would be able to.

HTTP/3 and its design tradeoffs

Now, consider HTTP/3, an implementation of the HTTP protocol that calls upon the QUIC protocol to transmit messages, in place of TCP. HTTP/3 was introduced shortly after QUIC, and developed in parallel with QUIC for the most part. As mentioned in Limitations of HTTP/2, HTTP/2 had a considerable “leak” from the transport layer up to the application layer with some considerable performance drawbacks. To remedy this, HTTP/3 had to address this leak by interacting deeply with the QUIC transport protocol (and vice versa), significantly more than HTTP/2 with TCP. Clearly, QUIC was designed with intention to work well for HTTP, as discussed in Where might QUIC be useful?. There, we saw that using QUIC would provide a client web application with an improved mobile browsing strategy.

This is a meaningful choice that the teams made when designing what would become the network stack that lives at HTTP/3. Without this tight coupling, HTTP/3 would not have been able to address the performance bottlenecks present in HTTP/2. This choice induced many nontrivial design challenges to be made while deploying the protocol at Internet-scale. While some of these challenges have been addressed, others remain open, particularly those related to security some are still open problems that must be addressed. The remainder of this section examines these challenges and relates them to broader design lessons drawn from the evolution of the Web.

Layering and backwards compatibility

HTTP/3 intends to implement the same semantics of HTTP, but over the QUIC protocol [11]. Therefore, it must be careful to not violate the features that old versions of HTTP expect. A significant benefit to holding the semantics constant is backwards compatibility. Old browsers can still use the same code to interface with HTTP at a high level. That is, components like the header format, status codes, and request methods are held constant, so the same routines can be reused to interface with this new protocol.

Clients of this protocol can therefore benefit from the performance improvements of HTTP/3 without considering how said improvements are achieved. At the top of the application layer, this leakage is largely hidden: substituting HTTP/3 for HTTP/2 does not alter HTTP’s correctness or semantics, even though HTTP/3 necessarily exposes some transport-layer behavior to the application through its integration with QUIC.

This depicts a great advantage in designing systems with layering in mind. Here, we are able to separate concerns and clearly evaluate the performance improvements of HTTP/3 relative to its predecessors. Browsers will continue to perform the same high-level routines to use HTTP (e.g. the GET method will still request a transfer of a current selected representation for the target resource [12]). As a result, any change in the performance can be determined as part of the work in the transport layer rather than at the application-level.

Even though HTTP/3 is deployed on the Web and offers performance improvements over its predecessors, it may not be supported by a given browser or client. Several factors can lead to this situation, most notably an out-of-date client or a user who explicitly chooses to continue using HTTP/2 for enterprise security reasons, say.

For this reason, existing protocols like HTTP/2 and HTTP/1.1 still must be supported. If these protocols were not supported, there would be significant network effects. That is, many of the links that the Web has created between documents would break if a server hosting some documents has stopped supporting the older protocols. In the spirit of Metcalfe’s Law [13], reducing protocol interoperability would fragment the network and diminish the overall value of the Web.

HTTP/3 supports these paradigms by occasionally removing assumptions on what protocol can be sent on the wire. A particularly interesting routine to determine HTTP/3 support acts as a great example of deployed backward compatible system routines using the principle of partial understanding. The routine is described below.

Suppose a client is unsure in which version to cooperate with a server

in. Then, to establish a performant connection over HTTP, the client

will initiate a connection over both TCP and UDP. This is a necessary

distinction from previous versions, since HTTP/3 connections are not

enabled over TCP. The server, if it supports HTTP/3 will use the

Alt-Svc header to indicate that an HTTP/3 connection is enabled over a

provided UDP port.

Then, the client, if it supports HTTP/3, will drop the TCP connection,

and initialize a UDP connection with the destination just specified by

the server. Now suppose the client does not support HTTP/3. Then, the

values in the Alt-Svc field will not encode any meaning to the client,

and the client will carry on with the TCP connection.

Therefore, this scheme captures the ability for HTTP/3 clients to find HTTP/3 servers to communicate with, while still allowing previous iterations of HTTP to communicate with those servers. This notion of backwards compatibility is excellent in that does not break links between clients and servers, but there are some tradeoffs.

Clearly, a TCP connection still needs to be established to potentially communicate with older versions---an apparent catch-22. That is, we tried to initialize a connection that avoids TCP by establishing a connection that uses TCP.

Indeed, this was later improved by relying on another system, DNS, to advertise HTTP/3 support. DNS Service Binding (SVCB) records enable authoritative servers to include supported protocols and connection parameters in a DNS response, allowing clients to discover HTTP/3 support without first establishing a TCP connection. [14; Section 7.1.2] This is a great optimization, as the supported protocols and hostname to IP address mapping will both be unknown if the hostname is not recognized on a client’s machine. Therefore, when resolving a hostname, you may not know the protocols supported by the machine that the hostname refers to. So, by performing the service binding within the DNS lookup routine, we are saving the work of setting a TCP connection by sending an HTTP/2 request to find supported protocols. This method also makes great choices in error handling. If the lookup does not resolve to any meaningful protocol (e.g. the hostname records did not include the service fields), the client can then fallback on whichever other resolution protocol that it wants to use. This is consistent with the fail mechanism in the aforementioned routine over TCP. That is, the client can decide whether or not to use HTTP/3. This consistency in the logic no matter the protocol makes a clean abstraction where the client can use various discovery subroutines for HTTP/3 without creating very different routines to initiate them.

These decisions demonstrate how HTTP/3 was able to live on machines that make up the Web without partitioning the Web by supported version. This was mainly done by enabling discovery of HTTP/3, which significantly does not enforce this protocol by default. So, all network traffic from old protocols can still operate as normal. This is a useful feature, since rollout of a new protocol for such a key service will be slow, since many may be hesitant to adopt it, as to avoid unknown security exploits, such as enterprise use cases. Discovery, though, is implemented with many different routines, the choice of which to use when is decided by the client. Therefore, the client, depending on what protocol they want to use, or what discovery method they want to use, can decide. The client may want to decide because they have their own performance gains or security gains that they want to choose the tradeoff between. This system, therefore, perfectly balances the separation of concerns between discovery, and acting upon the result of discovery.

OpenSSL and Node.js

Thus far, we have only considered “closed” problems that involve HTTP/3 and QUIC. These problems were addressed early on into HTTP/3’s release, the most recent one being the DNS service binding described in RFC 9460. However, since this is a new protocol, many large-scale, open-source applications find it difficult to collaborate on similar design choices. Such is the problem of Node.js, what StackOverflow reports as the web framework in which most developers have done work in as of late 2025 [15]. Node.js was seeking to implement HTTP/3, and therefore QUIC, in its runtime such that all the applications that use Node.js could make use of this new protocol.

The implementation of QUIC hit a blocker discovered by James Snell, a core contributor to the Node.js project and a member of the Node.js Technical Steering Committee, in an issue posed on the Node.js source code webpage [16]. Per the issue page, the problem is as follows:

HTTP/3 uses QUIC payloads to implement the TLS handshake, instead of over the TCP stream, as was standard in HTTP/2. On the other hand, a large suite of crypto routines previously used for crypto routines like TLS, OpenSSL, failed to add the necessary API calls to use TLS over QUIC payloads.

Here, OpenSSL’s implementations of TLS were sensitive to upward leaks from TCP, meaning that those implementations of TLS relied too heavily on TCP to accomplish their contracts.

The team behind Node.js, then, to move forward with HTTP/3 had to either choose to use another crypto suite, or wait for OpenSSL to update their API to support TLS-over-QUIC. Indeed, OpenSSL eventually did update their API, and Node.js contributors worked to implement this change.

This work was achieved over the course of over seven months, with many periods of little activity being done on the feature, as indicated by the sporadic timeline of messages in the thread [16]. From this, it seems that if these teams were more tightly coupled, this architecture work could have been done faster. This presents an argument in favor of centralized architecture, where teams that work on related technologies would be in more direct correspondence with each other. This way, efforts to deploy software at Web scale, as these projects do, would move quickly. With better communication, it would be easier to coordinate important decisions, too. When Node.js was faced with the decision to retain OpenSSL or replace it with BoringSSL (a forked project of OpenSSL that has implemented necessary API for TLS), many contributors disagreed on how to resolve the situation and it was hard to coordinate a solution on such a medium as GitHub issues, or discuss the issues in a timely manner [16]. Moreover, the feature cannot be confidently deployed as it has been in testing for a few months now.

Unfortunately, such a quick development process hard to accomplish as many of these developers are not primarily affiliated with Node.js. Rather, they are contributors to this open-source project that maintain it on a volunteer basis. So, progress does not move as quickly as it would with a tightly coupled team that wants to bring such technology to production for some economic gain.

Indeed, BoringSSL, the proposed replacement to OpenSSL, is developed by Google [17] who stand to gain greatly from QUIC and HTTP/3’s deployment since many of their sites like gmail.com can benefit from HTTP/3 support. QUIC, too, was initially developed by a team at Google [5]. On the other hand, BoringSSL was “designed to meet Google’s needs” [17] and likely was built to address such issues like the reimplementation of TLS-over-QUIC faster than OpenSSL themselves. Google would be more encouraged than the open-source contributors as they would know about the benefits of QUIC since they would be able to communicate the benefits in tightly coupled teams within the firm. Also, the developers for BoringSSL could coordinate much more directly within the firm with developers of QUIC, such that they can iterate on the dependencies of the protocol much faster together, such that they can deploy the protocol faster than the more latent open-source teams.

Therefore, although the improvements that QUIC makes to the network stack are substantial, they are organizationally hard to maintain by open-source developers, making such software harder to operate on in the open. This goes against what Sir Tim Berners-Lee posited in his autobiography, Weaving the Web: The Original Design and Ultimate Destiny of the World Wide Web by its inventor, where he stated that if there were overhead costs for development, people might be reluctant to developing standards or software for the Web, which would lead to reduced amounts of talent being involved in the design process of such an important system [18]. Such a phenomenon seems to be happening here with the barrier of development to update existing open-source web projects like Node.js by adding support for features defined in lower levels of the network stack.

Activities at the user level / kernel level

Another large debate throughout the development of HTTP/3 has been the tradeoffs between implementing security features like the TLS handshake in user applications or kernel applications. This distinction between running TLS in user space over QUIC and in kernel space over TCP is also a central reason behind the slow evolution of the OpenSSL API.

QUIC runs in user space as it is built over UDP, where UDP lives in kernel space [19]. So, too, does TCP and TLS over TCP. By a fundamental operating systems textbook, Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces, whenever an application must call a function in kernel mode and it is in user mode, it must resolve the function call with a trap handler [20; Section 6.2]. Transferring control, and computer state between kernel and user mode, though, takes time.

Moreover, QUIC, in user mode, does not have the same optimizations as transmissions over TCP, as the QUIC standard authors found [21]. They find that one issue with QUIC is that acknowledgement processing is an arduous process. With TCP, the acknowledgement process is processed at the kernel level, so the data required for the ACK does not need to be copied from user mode. However, they see that QUIC must copy from user to kernel mode upon context switching, which causes more time spent copying than TCP. Additionally, they find that TCP statefulness can be reused within the kernel on the machine, but the kernel does not yet maintain connection state for QUIC. So, the kernel still needs to look up the destination address IP, or check the firewall for special handling rules.

Therefore, the novelty of QUIC is creating this bottleneck since there is no kernel capabilities for the new protocol. Oku and Iyengar propose a solution to this bottleneck primarily by reducing packet size and reducing the acknowledgement frequency. Their proposal here was written in 2020, but it appears that it is still an open problem, as a draft standard has been published implementing this solution, but no action has been taken upon it [23].

Conclusion

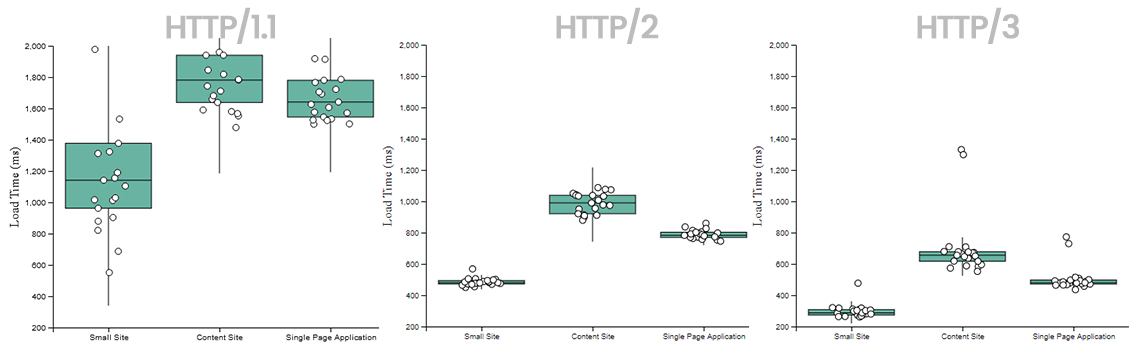

HTTP/3 has been effective in clearing bottlenecks of previous iterations

of the HTTP protocol by addressing the leaks that emerged between the

transport and application layer. The deployment of this new protocol has

been quite successful (see below), yielding significant and measurable

performance improvements. Because HTTP/3 is built on top of QUIC, many

of these gains are most pronounced in unstable or mobile networks, which

can be particularly useful in expanding access to the Web in developing

regions. Still, further optimization is still needed on this novel

protocol. In particular, improving mechanisms such as protocol discovery

and acknowledgement processing at the transport layer remains an open

area of work. As these problems are addressed with durable solutions,

HTTP/3 will continue to grow as a new backbone of the World Wide Web.

Querying a Digital Ocean server with various versions of HTTP, comparing performance. Sourced from [24].

References

[1] M. Thomson and C. Benfield, “HTTP/2,” Internet Engineering Task Force, Request for Comments RFC 9113, June 2022. doi: 10.17487/RFC9113.

[2] R. Peon and H. Ruellan, “HPACK: Header Compression for HTTP/2,” Internet Engineering Task Force, Request for Comments RFC 7541, May 2015. doi: 10.17487/RFC7541.

[3] J. Spolsky, “The Law of Leaky Abstractions,” Joel on Software. Accessed: Dec. 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.joelonsoftware.com/2002/11/11/the-law-of-leaky-abstractions/

[4] “Head-of-line blocking - Glossary | MDN,” MDN Web Docs. Accessed: Dec. 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Glossary/Head_of_line_blocking

[5] J. Iyengar and M. Thomson, “QUIC: A UDP-Based Multiplexed and Secure Transport,” Internet Engineering Task Force, Request for Comments RFC 9000, May 2021. doi: 10.17487/RFC9000.

[6] W. Eddy, “Transmission Control Protocol (TCP),” Internet Engineering Task Force, Request for Comments RFC 9293, Aug. 2022. doi: 10.17487/RFC9293.

[7] “Transport Layer Security (TLS) - Security | MDN,” MDN Web Docs. Accessed: Dec. 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/Security/Defenses/Transport_Layer_Security

[8] M. Thomson and S. Turner, “Using TLS to Secure QUIC,” Internet Engineering Task Force, Request for Comments RFC 9001, May 2021. doi: 10.17487/RFC9001.

[9] “Introducing QUIC Protocol Support for Network Load Balancer: Accelerating Mobile-First Applications | Networking & Content Delivery.” Accessed: Dec. 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/networking-and-content-delivery/introducing-quic-protocol-support-for-network-load-balancer-accelerating-mobile-first-applications/

[10] B. Schoon, “Google is removing basic HTML view from Gmail in 2024,” 9to5Google. Accessed: Dec. 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://9to5google.com/2023/09/25/gmail-basic-html-removal/

[11] M. Bishop, “HTTP/3,” Internet Engineering Task Force, Request for Comments RFC 9114, June 2022. doi: 10.17487/RFC9114.

[12] R. T. Fielding, M. Nottingham, and J. Reschke, “HTTP Semantics,” Internet Engineering Task Force, Request for Comments RFC 9110, June 2022. doi: 10.17487/RFC9110.

[13] S. Simeonov, “Metcalfe’s Law: more misunderstood than wrong?,” HighContrast. Accessed: Dec. 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://blog.simeonov.com/2006/07/26/metcalfes-law-more-misunderstood-than-wrong/

[14] M. Thomson and C. Benfield, “HTTP/2,” Internet Engineering Task Force, Request for Comments RFC 9113, June 2022. doi: 10.17487/RFC9113.

[15] “Technology | 2025 Stack Overflow Developer Survey.” Accessed: Dec. 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://survey.stackoverflow.co/2025/technology#1-web-frameworks-and-technologies

[16] “Update on QUIC · Issue #57281 · nodejs/node,” GitHub. Accessed: Dec. 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/nodejs/node/issues/57281

[17] google/boringssl. (Dec. 16, 2025). C++. Google. Accessed: Dec. 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/google/boringssl

[18] Berners-Lee, Tim, and Mark Fischetti. Weaving the Web: The Past, Present and Future of the World Wide Web by Its Inventor. Texere, 2000.

[19] “The Road to QUIC,” The Cloudflare Blog. Accessed: Dec. 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://blog.cloudflare.com/the-road-to-quic/

[20] R. H. Arpaci-Dusseau and A. C. Arpaci-Dusseau, Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces. Madison, WI, USA, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://pages.cs.wisc.edu/\~remzi/OSTEP/

[21] “QUIC vs TCP: Which is Better? | Fastly | Fastly.” Accessed: Dec. 16, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.fastly.com/blog/measuring-quic-vs-tcp-computational-efficiency

[22] Iyengar, Jana, et al. “QUIC Acknowledgment Frequency.” Quic Acknowledgment Frequency, quicwg.org/ack-frequency/draft-ietf-quic-ack-frequency.html. Accessed 16 Dec. 2025.

[23] “Examining HTTP/3 usage one year on,” The Cloudflare Blog. Accessed: Dec. 16, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://blog.cloudflare.com/http3-usage-one-year-on/

[24] “HTTP/3 is Fast!,” Request Metrics. Accessed: Dec. 16, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://requestmetrics.com/web-performance/http3-is-fast/